Cannabis as Medicine before Prohibition

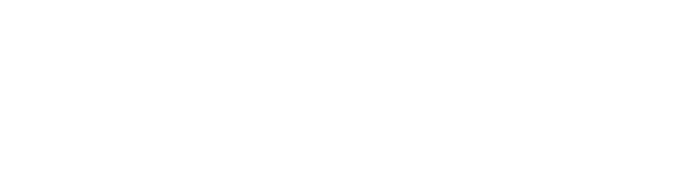

It is hypothesized that the use of cannabis for therapeutic or healing purposes predates written history; however, Chinese and Hindu written pharmacology has indicated that cannabis has been used for the last 12,000 years to relieve pain, reduce insomnia, treat wasting syndrome, reduce nausea, and stop seizures. The first recorded use of Cannabis as medicine was referenced in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia in 1500 B.C. For those of you who may not know, a pharmacopeia is a collection of descriptions of medications and their recommended uses. In this ancient pharmacopeia, it is described that a boiled hemp mixture called Rh-Ya was given to surgical patients as a form of anesthetic. Cannabis use in ancient times was also seen in Greek, Roman, and Indian cultures to treat conditions such as edema, earaches, malaria, inflammation, and rheumatism.

It was not until 1842 that Cannabis as medicine was introduced to western civilization by William O’Shaughnessy after his return from India working as an assistant surgeon. O’Shaughnessy was the first to write about THC-containing cannabis in Western Medicine. This Irish physician formulated cannabis tinctures to treat patients and described their effects while also conducting toxicity experiments on animals. By 1850 cannabis appeared in the U.S Pharmacopeia described to be useful in the treatment of several conditions such as gout, convulsions, typhus, opiate addiction, abnormal uterine bleeding, and more. What really helped legitimize cannabis use as medicine was Sir John Russel Reynolds prescribing cannabis to Queen VIctoria to help ease her menstrual cramps. For decades after this cannabis was widely used for industrial and medicinal purposes due to its cheapness and availability. Unfortunately, by 1911 Massachusetts became the first U.S state to officially declare cannabis as a dangerous drug and ban it.

The Precursor to the War on Drugs

Many of you may be wondering what led to the prohibition of cannabis considering the plant was used as a medicine for centuries. Like many injustices in America, this prohibition stemmed from misinformation, intolerance and xenophobia. You may have heard the terms ‘cannabis’ and ‘marijuana’ used interchangeably. While many individuals still use both terms, scientists, activists, and cannabis industry professionals realize that “marijuana” is a historically racialized term used by government officials and media personalities to turn public opinion against cannabis and an entire group of people. The term “marijuana” or “marihuana” is Spanish, originated in Mexico, and has been used as a slang term to describe cannabis. Tensions between Mexico and the U.S were high during and after the Spanish-American War in 1898, leading to negative portrayals of Mexicans in the media and among politicians and government officials. One stereotype pushed during this time was that “Mexicans use Marihuana” and media outlets found it easy to blame Americas new immigrants for the rising crime, ultimately allowing civilians to draw the conclusion that “marihuana” is dangerous.

Dosing difficulties and other standardization issues also started to become an area of concern. Unlike other medications, cannabis is not water soluble, therefore it cannot be formulated for intravenous use like other medications and pain killers. While it is possible to determine the strength of a cannabis dose through titration, these formulations separated after sitting and led to published reports of overdosing and hallucinations. These reports only added more fear into the minds of the American population.

The laws passed in the early 1900’s laid the groundwork for a sort-of domino effect leading to the prohibition of cannabis. In 1906 Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, making this the nation’s first effort to regulate and standardize commercial drugs, foods, and other products. This act did not outlaw marijuana, it only empowered the U.S Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Chemistry to test and regulate substances, leaving a significant impact on cannabis. Not too long after this, Congress passed the Opium Exclusion Act of 1909. This act was motivated by racism and stemmed from disputes with Chinese immigrants. To many, The Opium Exclusion Act signifies the beginning of the War on Drugs because the banning of opium was soon expanded to other drugs. In 1914 Congress passed the Harrison Act. This act allowed the government to keep account of prescriptions and created penalties for doctors who violated this act by dispensing or prescribing substances without permission or without paying taxes. These laws were the introduction of drug control policies being enforced through taxation. Next, in 1922 the Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act was passed. This act established the Federal Narcotics Control Board, expanded criminal penalties for illegal importation, and put restrictions on the ability to export narcotic drugs. Just a few years later, the Porter Narcotic Bill was passed in 1930. This bill closed the Narcotics Control Board and transferred all of the powers of the Bureau of Prohibition to the New Bureau of Narcotics within the Treasury Department, which later became The Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This act was the catalyst that shifted drug control policy away from taxation and into the early stages of prohibition.

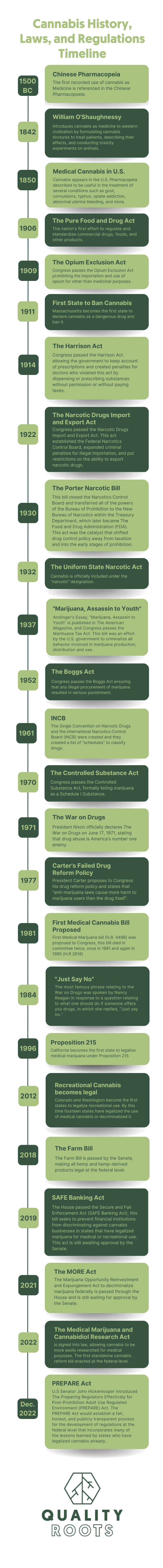

Now, you may be wondering what cannabis has to do with all these narcotic drug laws and regulations. Well, we’re getting to that. 1932 is the year that cannabis was officially included under the “narcotic” designation with the Uniform State Narcotic Act. Even before this, state-level bans on cannabis were popping up left and right, starting with Massacusetts in 1911. At this point, the big, bad wolf of cannabis prohibition comes into play – Harry J. Anslinger. Anslinger became the first commissioner of the newly established Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) where he was able to create the greatest impact on drug policy and prohibition in the twentieth century. Anslinger manipulated data and formulated statistics to make cannabis seem more dangerous than it is. Again, racism comes into play and becomes a common weapon in Harry’s arsenal against “marijuana.” In many of his essays he points fingers at Mexico for bringing this “dangerous drug” to America and tries to scare the American public into thinking that smoking “marijuana” will turn people into criminals and murderers. In Anslinger’s 1937 Essay titled “Marijuana, Assassin to Youth” he writes,

“There should be campaigns of education in every school, so that children will not be deceived by the wiles of peddlers, but will know of the insanity, the disgrace, the horror which marijuana can bring to its victim. There must be constant enforcement and constant education against this enemy, which has a record of murder and terror running through the centuries.”

Anslinger spent his 30 years as the commissioner of the FBN working to instill fear and prejudice towards cannabis and its users into the minds of Americans, and it worked. The same year Anslinger’s essay was published in The American Magazine, Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act. This bill was an effort by the U.S. government to criminalize all behavior involved in marijuana production, distribution and use. By the 1950’s marijuana, and other drugs, were legal but extremely difficult to procure. The Boggs Act of 1952 ensured that any illegal procurement of marijuana resulted in serious punishment.

The Counterculture Movement and the Declaration of the War on Drugs

The counterculture movement of the 1960s brought dramatic social change to the U.S and led to increased criminalization of drugs, marijuana being at the forefront. Before the hippies of the sixties prevailed, the 1956 Eisenhower Report was published. This report aimed to investigate the depths of harm that drugs have on society and establish an administrative state that would punish violators with harsh sentences.

In 1961 The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was created. Through this convention, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) was born. The board developed a list of “schedules” to classify drugs into categories based on relative levels of danger, putting marijuana at the top of the list alongside the most dangerous and addictive substances like cocaine and heroin. By 1970, the Controlled Substance Act formalized drug scheduling and listed marijuana as a Schedule 1 Substance. Schedule 1 substances are defined as substances “have a high potential for abuse, have no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and there is a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug under medical supervision.” Still today cannabis is considered a Schedule 1 substance even though it has been proven that cannabis has a very low abuse potential, may help in the treatment of several medical conditions, and it is deemed safe to use with and without medical supervision.

At the tail end of the sixties with President Nixon now in office and the hippie movement still forging on, this is when The War on Drugs truly begins. Nixon declared his War on Drugs June 17, 1971, stating that drug abuse is America’s number one enemy. Nixon, the leader of this war, appointed Congress responsible for fighting this enemy, and their efforts proved successful. In 1972, Nixon was reelected, winning more votes than any other President up to that point. Nixon used his first State of the Union Address to discuss the importance of drug abuse prevention and oppose marijuana legalization. After Nixon’s resignation in 1974, President Ford took office and carried on Nixon’s work for the War on Drugs.

It wasn’t until President Carter took office in 1976 that a push towards drug reform and libertarianism arose. Carter, with the support of Dr. Peter Bourn, a known drug treatment specialist and reformer, called for marijuana decriminalization in the United States. In his 1977 proposal to congress, Carter pointed out that “anti-marijuana laws cause more harm to marijuana users than the drug itself.” In this proposal to Congress, Carter touched on 5 more critical issues involving drug reform. Firstly, the aim of Carter’s drug reform policy was to focus federal attention on drugs that were statistically proven to pose the greatest threat to health, and to our ability to face crime; such as heroin and other sedative/hypnotic drugs. Carter wanted to streamline drug policy jurisdiction for better efficiency. Carter also argued that the federal government had become too involved in policing drugs and pushed to reevaluate the results of this effort to determine whether federal participation should be altered. Carter wanted to look at drugs from a holistic viewpoint and focus on rehabilitation for drug abusers rather than criminalization. Lastly, Carter acknowledged serious gaps in drug research in the United States. Sadly, these reform proposals were never enacted. Dr. Bourne became involved in a political scandal and an inflation crisis swayed Carter’s attention away from marijuana reform.

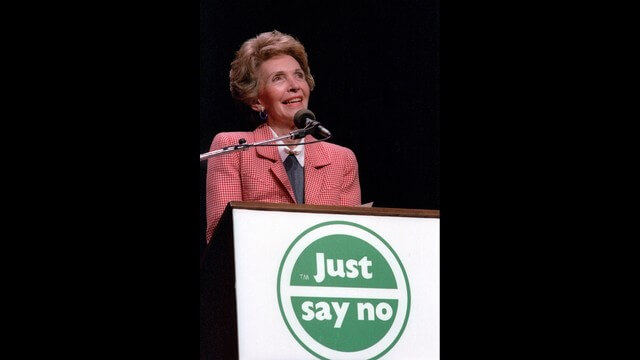

The early 1980s began the resurgence of the War on Drugs with the Reagan Administration, and these efforts were expanded internationally. The Reagan Administration, the DEA and other agencies wanted to eradicate drugs at the source and extended anti-drug operations into Columbia, Mexico, Honduras, Panama and other Latin American nations. In 1984, arguably the most famous phrase relating to the War on Drugs was spoken by Nancy Reagan in response to a question relating to what one should do if someone offers you drugs, in which she replied, “Just say no.” This term was coined and used for a historic messaging campaign focused on demonizing drug-use, targeting the American youth.

Medical Marijuana enters the discussion

While the War on Drugs and “Just Say No” campaigns were at the forefront of the media, some government officials were still working on drug reform behind the scenes. In 1981 the first Medical Marijuana bill was proposed to Congress. H.R. 4498 was a bill to provide for the therapeutic use of marijuana in situations involving life threatening illnesses and to provide adequate supplies of marijuana for such use. Unfortunately, this bill died in committee and was proposed again in 1995. H.R. 2618 was proposed, stating the same legislation as H.R. 4498 but included the rescheduling of marijuana to Schedule II. This bill also defined qualifying conditions for medical treatment using marijuana including cancer, glaucoma, AIDS wasting syndrome, and spastic disorders of the muscles. Again, this bill died in committee.

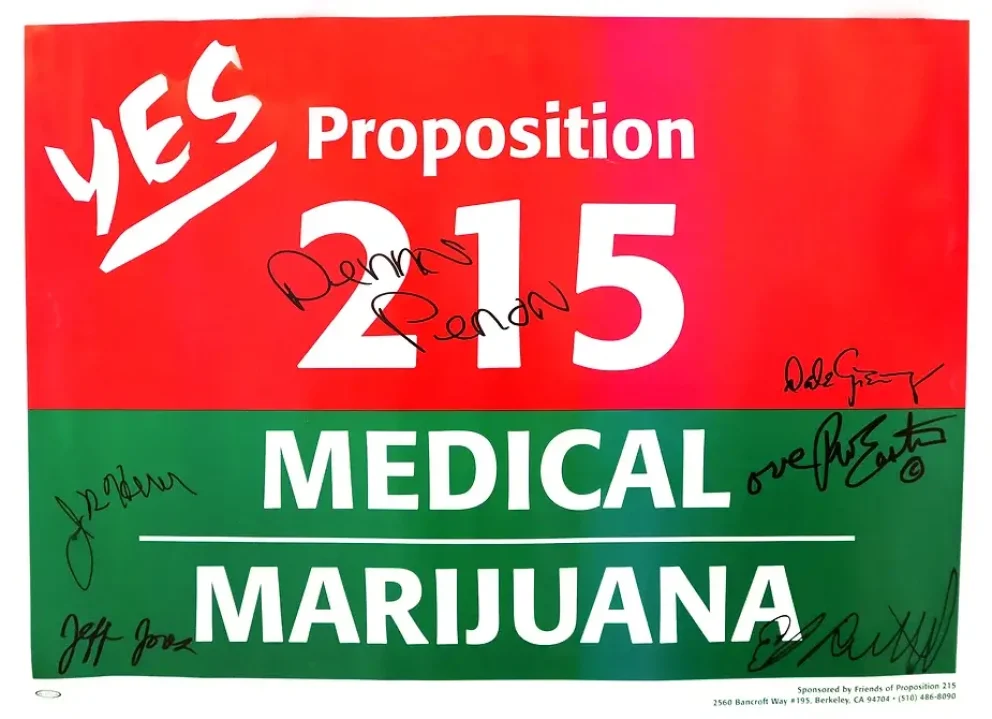

While nothing substantial is happening at the federal level in regards to medical marijuana reform at this time, many advancements are happening at the state level. In 1996, California became the first state to legalize medical marijuana under Proposition 215, also known as the Compassionate Use Act. By 2012, fourteen states legalized the use of medical cannabis or decriminalized its use, and Colorado and Washington became the first states to legalize recreational use.

The Recent Years

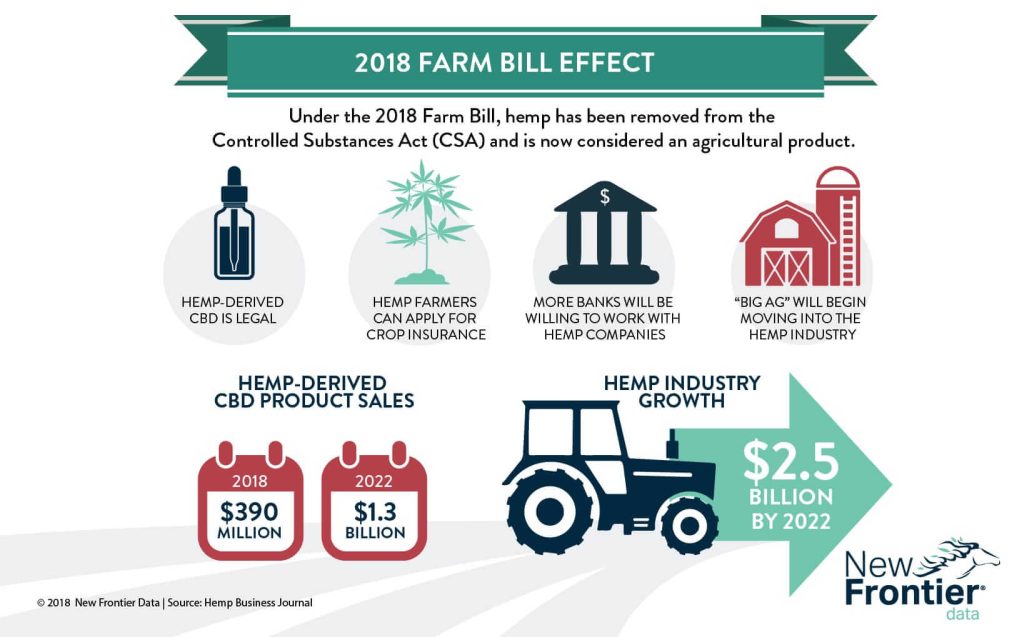

2014 is the year that brought light to the federal marijuana reform efforts when the House approved the Rohrabacher-Farr amendment. This amendment has been signed into law and prohibits the Department of Justice from using funds to prevent states from implementing their own state laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession or cultivation of medical marijuana. After this, the House and Senate separately began taking up marijuana legislation more frequently. The 2018 Farm Bill was passed and signed into law, legalizing hemp and hemp-derived products at the federal level, de-scheduling and removing hemp from the Controlled Substance Act where it was formally listed as a Schedule I substance.

In 2019 the House passed the Secure and Fair Enforcement Act (SAFE Banking Act). This bill seeks to prevent financial institutions from discriminating against cannabis businesses in states that have legalized marijuana for medical or recreational use. This bill was passed by the House but is awaiting approval from the Senate. In the same year, the House Judiciary Committee approved the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act (MORE Act). This proposal decriminalizes marijuana; more specifically, it removes marijuana from the list of scheduled substances under the Controlled Substances Act and eliminates criminal penalties for an individual who manufactures, distributes, or possesses marijuana. This bill would also tax marijuana federally to use those taxes to invest in areas such as job training, literacy, and substance abuse treatment. The MORE Act also replaces references to ‘marijuana’ and ‘marihuana’ with ‘cannabis’. Excitingly, in 2021 this bill was passed through the House and is currently waiting for approval by the Senate. Most recently, in 2022 The Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act was signed into law. This allows cannabis to be more easily researched for medical purposes and is the first standalone cannabis reform bill enacted at the federal level.

What Comes Next?

With the possibility of cannabis becoming legal at the federal level it is important to make sure that there are plans in place to ensure safe and effective regulations. In December of 2022 U.S Senator John Hickenlooper introduced The Preparing Regulators Effectively for Post-Prohibition Adult Use Regulated Environment (PREPARE) Act. The PREPARE Act would establish a fair, honest, and publicly transparent process for the development of regulations at the federal level that incorporates many of the lessons learned by states who have legalized cannabis already. This bill would specifically direct the Attorney General to establish a “Commission on the Federal Regulation of Cannabis” to advise on the development of a regulatory framework modeled after existing federal and state regulations for alcohol. The framework would have to account for the unique needs of each state and be presented to Congress within one year of the enactment of the PREPARE Act. The regulatory framework would have to include ways to remedy the impact cannabis prohibition has had on minority, low-income, and veteran communities; encourage research and training access by medical professionals; encourage economic opportunity for individuals and small businesses; and develop protections for the hemp industry.